Are Chinese consumers really spending heavily? Data suggests it is the rich who are consuming, not the masses. (Photo by Akira Kodaka)

BEIJING — China’s transition to an economy driven by consumption, rather than investment, is complete — at least according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Mao Shengyong, a bureau spokesman, on Dec. 14 told reporters that while investment and exports used to fuel growth, consumer spending is now leading the way. The latest numbers seem to back him up: Consumption accounted for as much as 64.5% of gross domestic product growth in the first nine months of 2017, which is 2.8 percentage points higher than the same period a year ago.

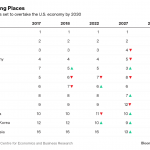

Generally, emerging economies rely on investment and exports, before shifting to consumption-driven models as they mature. Chinese President Xi Jinping has emphasized this transition as a key to achieving “high-quality development.” And global companies have been swooping in, determined to cash in on a Chinese consumption boom.

But a closer look at China’s economy over the past three decades reveals that consumption was already a major engine in the past. From 1987 to 2016, consumption contributed more to China’s annual GDP growth than investment 20 times.

Only around the turn of the century did the country become heavily dependent on investment: From 2000 to 2010, investment made a higher contribution in seven years. Those were the years in which China joined the World Trade Organization (2001) and was eager to show growth, and when the government pulled all its levers to blunt the impact of the global financial crisis.

Now it appears that China is shifting back to a consumption-led economy. But are consumers really doing the heavy lifting? Probably not. The shift occurred simply because investment growth has reached a saturation point.

Investment dependency

Even if overall consumption is contributing more to GDP now, China is still heavily dependent on investment and continues to grapple with the side effects of its addiction.

Since 2008, when Beijing countered the global financial crisis with a stimulus package worth 4 trillion yuan ($610 billion at the current rate), investment has continued to account for more than 40% of GDP. This is an unusually high percentage for a large economy. The comparable figures for developed countries are around 20%.

Meanwhile, China’s ratio of consumer spending in GDP has been stuck below 40% since 2005. The percentage was hovering above 50% in the 1980s, but it has not surpassed 50% since 1990.

Few people were walking in “China’s Manhattan” this November. (Photo by Issaku Harada)

A symbol of the investment addiction can be found in “China’s Manhattan.”

Tianjin’s Conch Bay, a 110-hectare district with a cluster of 40 high-rise buildings, was supposed to be the country’s new financial capital as outlays surged over the past several years. But in late November there were few signs of life. A number of buildings were still under construction; the streets were empty; and even completed buildings had no occupants.

From 2000 to 2010, investment in Tianjin — the hometown of former Premier Wen Jiabao — swelled by a factor of 10.3. Investment in Beijing also jumped in the same period, but only 3.6-fold, even though the capital was preparing to host the 2008 Summer Olympics.

“At the time, there were a host of national projects and investment was a priority,” one Tianjin municipal government official said. “We realized later that Tianjin lagged behind other cities in terms of technological innovation and research and development.”

Widening gap

At first glance, consumption in China appears to be gathering steam, as exemplified by strong online shopping sales on the Nov. 11 Singles Day. But total retail sales of consumer goods increased just 8.8% in real terms in November, which was much slower than the 12% growth of 2012.

Sluggish growth in middle-class income is seen as one factor behind the weakening trend of consumption.

To understand what is happening in China, note the distinction between “average” and “median” household incomes.

The average household’s disposable income rose 9.1% on the year in the first nine months of 2017 — beating the growth rates in 2015 and 2016.

But the median disposable income rose only 7.4%, which is probably a more accurate reading of the economy.

Say there are 100 households. The median disposable income is that of the household with the 50th-highest figure. If one household with an income of $1 million were to join 99 households making $10,000 each, the average income would balloon but the median would remain the same.

In China, where wealth is concentrated in Communist Party cadres and those close to them, the average is meaningless because the rich distort the reading. What matters is the median.

The property bubble in big cities in 2016 produced new billionaires, pushing up the average further and widening the gap between the rich and the middle class.

Consumption patterns suggest that the masses are reluctant to spend: The stock price and sales of China’s top liquor producer, Kweichow Moutai, are close to all-time highs, as demand for high-end baijiu remains brisk. Yet, regular baijiu is not riding the same tail wind.

Sales of instant noodles, a staple for households with lower incomes, have declined for three years in a row. The Chinese beer market also has seen a three-year decline, yet demand for premium beer is robust.

Therefore, although it may look like consumption is becoming a stronger driver of the economy, the wealthy are playing a disproportionate role. The other worry is the mounting household debt that appears unsustainable.

Chinese households were saddled with the equivalent of 47% of the country’s GDP at the end of June, up 28 percentage points from a decade earlier.

That ratio is still lower than the 78% in the U.S. and 57% in Japan, but the International Monetary Fund has warned that the sharp rise in Chinese household debt is reminiscent of what happened stateside before the collapse of Lehman Brothers at the onset of the global financial crisis.

Many middle-class Chinese families have taken out hefty mortgages to buy property amid surging prices, making them reluctant or unable to spend on other things.

“I am concerned about my pension, medical care and education fees for my children,” said one public servant who recently purchased a house in a Beijing suburb for 3.5 million yuan. “I cannot open my wallet easily.”

[“Source-nikkei”]