When we meet with people who are considering whether to hire our firm as their new investment manager, there is one predictable question. They wonder aloud whether they should just put all their money in an index fund and leave it there. They then turn to me and ask what I think of that.

I take a deep breath. As an active money manager, I put work into building a portfolio to beat the benchmark, not just track it. But rather than getting annoyed and ruining an opportunity, I have taken the time to craft a response that might be useful to our readers.

First, I would offer one piece of advice to my colleagues in the business of active management, whether old-fashioned, long-only investing or hedge funds: Showcasing past outperformance is important but not the most compelling case to make. Whatever record we have compiled in the past is no guarantee of the future. You may hit a rough patch and underperform. The reputable index fund matches its benchmark day in and day out.

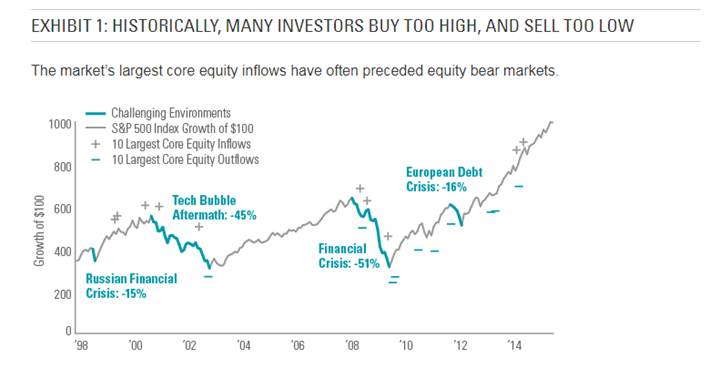

My advice is to highlight the evidence around human behavior. Individual investors who own mutual funds historically underperform the overall return of those same mutual funds. For example, a study from 2016 cites 30 years during which the S&P 500 returned 10.35 percent annually but individuals only gained 3.66 percent per year. While there are many causes for this gap, the most significant is being human, accounting for 1.5 percentage points

Even fund expenses, widely decried as egregious, cost investors about half that in any given year.

It is no surprise that individuals left to their own devices enthusiastically buy into hot markets and abandon ship at the worst possible time. While most participants acknowledge the benefit of a consistent buy and hold strategy, temptation, greed and fear are overwhelming motivators. Just consider that the losses from 2008 were so psychologically and financially damaging that it took seven years of a bull market to induce retail investors back into the water.

These findings are similar whether analyzing investor returns in actively managed funds or index funds. The fact that many of these passive funds are low cost might even encourage participants to trade more, further dampening performance. Passive mutual fund investors are obviously not as passive about their ownership stakes in these underlying funds.

How does this data contribute to my response about active versus passive investing? The evidence clearly indicates that individuals are poor market timers and emotionally driven to often make bad decisions.

However, it’s difficult to say whether professionals claim a more level-headed approach. Training and experience should lead to less panic selling and overdrive buying. We know there is a strong survival bias in our industry. Firms that sold at the bottom in 2009 and never reinvested the cash may well have disappeared by now.

While some studies suggest that professionals are not prescient market timers, although better than amateurs, one indicator of level-headedness would be cash levels. We all have a record of our cash deployment and raising. This applies to managers who actively make individual stock decisions as well as those who use index funds or ETFs. It might be wise for client prospects to inquire about our trading behavior, turnover and allocations in 2008 and 2009 and through the subsequent lengthy bull market.

So, when asked why it’s better to have a professional invest their money, I reference human behavior. It was a perfectly acceptable choice, if you were from New England, to leave the Super Bowl party in 2017 at the end of the third quarter depressed and frustrated because the Patriots were down by 25 points. It seemed smart to sell airline stocks when ebola fear was at a frenzy or to dump Puerto Rico bonds in mid-2017. These were emotionally consistent moves, but history shows they were definitely not the right moves.

[“Source-cnbc”]