Outside the COPO plant in Oxford, Michigan, Tyler Mitchell drives his father’s new COPO into a trailer to be hauled to their Indiana home.

Photographer: Nick Hagen/Bloomberg

Living out your childhood dreams doesn’t come cheap. Just ask Kevin Mitchell.

When he was in sixth grade, his parents got him a set of wrenches. As a high-schooler, he rebuilt a 1967 Chevrolet Camaro SS that he raced around the back streets of Danville, Illinois.

Now 54, the owner of an electrical contracting business, Mitchell has built up a collection of cars that includes five Corvettes, a Lamborghini Diablo, and several Camaros. And while he isn’t afraid to get under the hood, he’s more interested in driving them.

So when he got an April Fool’s Day email saying he was one of 69 people randomly chosen in a lottery of more than 3,000 for a chance to buy a special COPO-edition Camaro, he thought to email Curt Collins, who runs Chevy’s high-performance car program, before getting too excited.

“I asked him if it was a joke,” Mitchell said. It wasn’t. “I couldn’t believe I got one.”

The COPO Camaro is the most exclusive car General Motors Co. sells, a fact even a well-versed gearhead could be forgiven for not knowing. These drag racers are hand-built in small numbers for track use only, and no cajoling can get a buyer through the random lottery. They’re marketed to the most diehard Chevy fans, the kind who want to race one, run it on a performance track, or add it to a collection of shiny toys.

Ford sells a similar package, the Mustang Cobra Jet, albeit with less fanfare, and Dodge sells a version of its Challenger muscle car with a Drag Pak—extra equipment for the race-minded buyer. Ford has an outside firm turn its Mustang bodies into race cars, and the Cobra Jet isn’t built every year; when it is, it comes in in batches of 50 with each car selling for just under $100,000—and not by lottery—said spokesman Matt Leaver.

Chevy has managed to gin up more enthusiasm for its COPOs than other such programs have for their cars by holding its lottery, playing up the cars’ 1969 heritage and making the final sale an event for buyers, said Peter DeLorenzo, whose website Autoextremist.com covers both the industry and racing.

Each car takes 10 days to build; a regular Camaro rolls off the assembly line after maybe 20 hours of work. Each COPO is numbered, like an art print or a special-edition bottle of high-end bourbon; buyers of such rarities like to know that what they’re getting is special. Each goes for at least $110,000, and much more at auction.

Of GM’s priciest cars, only a fully loaded Corvette Z06 costs nearly as much. No Cadillac comes close. “Few people get out of here for much less than $130,000, and some spend as much as $200,000 on options,” Collins said.

Mitchell, about $125,000 later, was headed to the tiny plant north of Detroit where they’re built with his son Tyler and a trailer (the cars aren’t street legal) to haul home COPO No. 47, of 69.

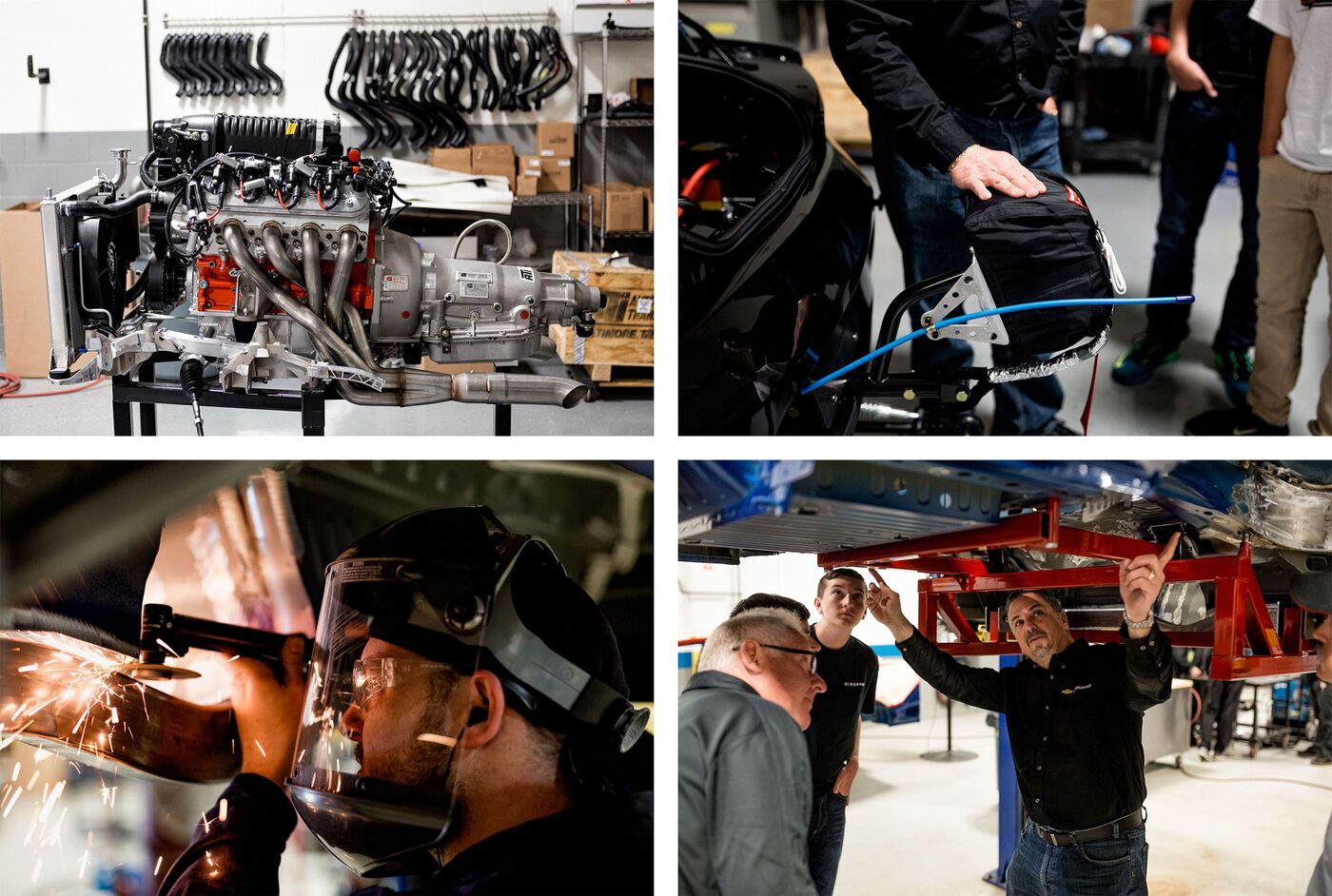

From out front, the COPO plant, in its small strip of office buildings in suburban Oxford, Michigan, looked less like an auto plant than someplace geeks might go to find rare computer parts. The only giveaway was a handful of still-unpainted steel Camaro body shells lined up outside—the only parts that come from the Camaro plant an hour away in Lansing. But the scene inside recalled one from “Grease”: cars on lifts, classic rock playing as 20 mechanics and craftsmen banged away and welded the cars together.

The COPO story goes back to 1969, when a few crafty Chevy dealers figured out they could custom-order some Camaros with Corvette engines from GM’s central office. Each special production order was called a Central Office Production Order, or COPO. GM shut down the program after just a few years but revived it in 2012.

The cars have been collectors’ items ever since. The company sold COPO No. 1 at Barrett Jackson’s exclusive car auctions in 2014 for $700,000 and gave the proceeds to different charities. The next year, car No. 1 for the 2015 model year went for $300,000. Since the cars aren’t street legal, they’re sought after by collectors who rarely even start them up and by amateur race car drivers.

“A lot of the amateur drive guys buy these cars so they don’t have to build a race car and be concerned with safety,” DeLorenzo said. “These buyers want to spend more time running the cars than working on them.”

That’s Mitchell’s plan. He started racing a 1969 Camaro last year but aspired to race in the National Hot Rod Association’s amateur drag events. He plans to start with an Independent Hot Rod Association race in Morocco, Illinois. If he shows he’s a safe and skilled-enough driver, he can get his racing license and head to the NHRA.

COPO drivers need skill. Depending on the engine they choose, they can kick with 410 horsepower and up to 580. Unlike a common Camaro, the COPO has special racing seats, with a harness and a steel roll cage inside for extra protection in case of a crash. “There is nothing on the car like you get on a stock Camaro,” Collins said.

The car is actually engineered to race in NHRA races, Collins said—it’s all about going fast in a straight line. There’s no airbag, no power steering, no power brakes, no anti-lock braking system. The fuel tank is just six gallons, since it’s used only for racing or track time. If you want, you can order a parachute to give the car some drag and slow it down after crossing the finish line.

Mitchell opted for one. Inside the plant, as he circled his new red-and-black drag racer for an inspection, he checked out the parachute in the trunk. Then he went to climb into the driver’s seat—and it quite literally was a climb. The roll bars swung through the doorway; he had to slip over them to get in. He’s not quite as lean as he was as a track-running, Camaro-racing teenager; back then, he might have had an easier time.

His son snapped photos of the car as he squirmed over the bars. “Don’t anyone take a picture of this,” he said.

[“Source-ndtv”]